Unlocking value through solar PV repowering: A focus on module replacement and DC/AC optimisation

by David Fernandez

View post

This blog post is the second in a four-part series unpacking the key pieces of information from the IPCC AR6 reports. Part one - The latest climate science from the IPCC. Part three - How to keep global warming to within 'safe levels'.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) produces a set of major reports every seven years summarising the latest climate science and its implications for human society. It is currently in its sixth assessment report cycle (AR6).

In February 2022, the IPCC released the second report in the series, AR6 Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. This report examines climate change impacts so far and how it will impact the world in the future. A key dimension to the report is how humans can adapt to climate change.

Given the intervals between reporting cycles, this will most likely be the last IPCC Assessment Report before the 1.5°C temperature threshold is breached.

Key highlights from the report:

Perhaps unsurprisingly given the stark conclusions of this mounting body of evidence, more data has emerged of the detrimental impacts of climate change on mental health. Heat is “one of the best-studied aspects of climate change observed to reduce wellbeing”, according to the report. It says that increasing temperatures are linked to higher hospital admissions for mood and behavioural disorders, “experiences of anxiety, depression, and acute stress” and suicide rates. A recent study suggested higher temperatures are reducing people’s average sleep time. Sleep is widely acknowledged to be key to health and wellbeing.

What does the report say about the necessary adaptation?

The report says that, “gaps exist between current levels of adaptation and levels needed to respond to impacts and reduce climate risks”. In other words, climate adaptation is currently insufficient. This is largely due to the focus that has thus far been placed on climate mitigation.

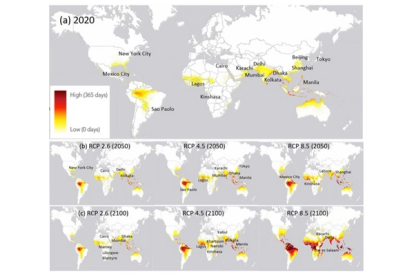

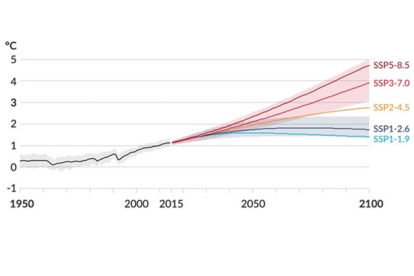

As we are witnessing, climate change is already having a significant impact around the world. Even in the very best case scenario where emissions peak in the next 10 years, it is important to keep in mind that there is a time lag of approximately 10 years between when emissions are released into the atmosphere and the ensuing temperature rise. This is why the various different scenarios look quite similar until the latter half of the 2020s.

Focusing on heat and drought stress on crops, the report says: “Substantive agricultural production losses are projected for most European areas over the 21st century, which will not be offset by gains in Northern Europe (high confidence). While irrigation is an effective adaptation option for agriculture, the ability to adapt using irrigation will be increasingly limited by water availability, especially in response to global warming above 3°C (high confidence).”

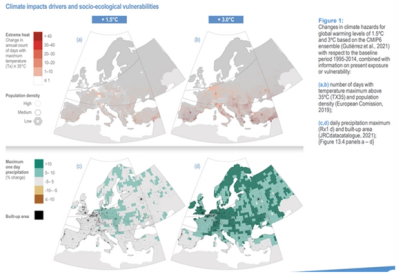

The factsheet provides an indication as to the differences between 1.5°C and 3°C for extreme heat and maximum one day precipitation, i.e., the amount of rainfall that can occur in a very short period of time. As can be seen the in the diagram below, a 3°C scenario increases the area prone to experiencing extreme rainfall significantly across Europe.

The factsheet also offers solutions such as: “irrigation, vegetation cover, changes in farming practices, crop and animal species, and shifting planting; [fire and forest management, and agroecology]”.

It also documents key barriers as: “limited resources, lack of private sector and citizens engagement, insufficient mobilisation of finance, lack of political leadership, and low sense of urgency. Most of the adaptation options to the key risks depend on limited water and land resources, creating competition and trade-offs, also with mitigation options and socio-economic developments (high confidence).”

Importantly, the report also discusses residual risks, i.e., risks that cannot be mitigated. It states that, “residual risk can result in losses of habitat and ecosystem services, heat related deaths, crop failures, water rationing during droughts in Southern Europe, and loss of land (medium confidence).”

What does this mean for companies, investors, and individuals?

Firstly, when one is proverbially in a hole, stop digging - so the age-old adage goes. That means all organisations and individuals need to mobilise to cut emissions as soon as possible. They can also support a wider network effect by signalling to others that they are taking pro-active action to cut emissions. Whilst all actions that reduce emissions are good, actions that support systemic changes should be prioritised. For example from a personal perspective, reducing meat consumption is good, explaining to your friends and family why you are doing it and encouraging them to do the same is has an even more powerful network effect. The same could be said for flying, switching to a renewable energy provider, driving less, voting for politicians with ambitious climate polices etc.

For many organisations, one of the easiest and most impactful ways to cut emissions is by switching to a renewable energy provider. For investors, their impact is concentrated in their portfolios, so exploring ways to support investee companies in their net zero transition is key. This is something our net zero specialists can support you with here at SLR.

Looking to the impacts of climate change and how to adapt to them, performing a climate change risk assessment is a sensible first step, followed by embedding effective risk management into existing systems. The ISO14090:2019 Adaptation to Climate Change standard provides a helpful framework for organisations to consider.

At SLR, we recently assessed climate risk under different scenarios for a $450bn pension fund, focusing on their most significant coastal assets. The main surprise for the client being the speed with which risks such as sea-level rise and storm surges could materialise, even in low-emissions scenarios. It is important for organisations to consider that risks may occur in the short to medium term, and need to be planned for today.

For support with climate change risk assessments, climate scenario analysis, developing your organisation’s climate strategy and capacity or responding to the TCFD reporting requirements please contact us.