Understanding and Protecting Short-Range Endemic Terrestrial Invertebrates

- Post Date

- 12 January 2026

- Read Time

- 15 minutes

Terrestrial invertebrates make up 80% of the faunal biota, yet often go unnoticed (Braby, 2018). The impact on these small animals may be far greater than that of their more conspicuous and well-known vertebrate counterparts (i.e., mammals, birds, and reptiles). Without proper management, some species restricted to single, isolated habitats are at heightened risk of extinction from land clearing projects. These disturbances can trigger cascading effects, with implications for food chains, biodiversity, and compromising ecosystem services.

The invertebrate fauna group is highly diverse and contains many species with specific evolutionary adaptations, allowing them to occupy extremely niche microhabitats (Braby, 2018). Adding further complications to this, many species have highly restricted distributions and are therefore considered to be short-range endemics (SREs).

What is a SRE?

An SRE is defined as having a known distribution of < 10,000 km2 (Harvey, 2002), with some groups of animals known to contain a higher proportion of restricted range species than others. These are referred to as the SRE groups (Harvey, 2002). It is these species with highly restricted distributions that are more susceptible to anthropogenic disturbance through land clearing and habitat removal (EPA, 2016; Harvey, 2002; Ponder, 1997).

Why are they important?

Invertebrates play a vital role in maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem function, with many being considered as Keystone species (Majer & Framenau, 2017). In fact, this group of animals have long been referred to as “the little things that run the world” (Wilson. E, 1987). The small size and diversity of invertebrates mean they can form small niches within the environment allowing for more species to coexist within the landscape, adding to the biodiversity of any given region (Wilson. E, 1987).

How do we decide if something is a SRE?

SREs tend to be:

- Ground-dwelling

- Poor at dispersing

- Active only during certain seasons, often after rain

- Low in reproduction

- Living in broken or isolated habitats

They prefer sheltered places that hold moisture longer than the surrounding landscape. These include rock outcrops, gullies, south-facing slopes, drainage lines, vine thickets, islands, or semi-arid areas where moist habitats are rare (EPA, 2016; Harvey, 2002; Durrant, 2011).

Some examples are:

- Selonopid spiders and certain snails are found only in rocky habitats, which were recently listed as a Priority Ecological Community (PEC) by The Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA, 2025).

- Snails living in vine thickets or swamps, listed as Priority Ecological Communities (PECs) or Threatened Ecological Communities (TECs) by DBCA.

However, understanding what constitutes a single species can also be challenging. In 2018, Johnson & Stankowski discovered that seven snail species were actually one species with different shell shapes depending on their habitat. Conversely, some species considered single have been split into multiple species after studying internal anatomy or genetics (Buzatto et al., 2023; Castalanelli et al., 2014; Rix et al., 2018).

Cryptic Species

Cryptic characteristics are common within the SRE groups and are not necessarily limited to morphology of specimens alone. For instance, Mygalomorph spiders inhabit burrows, many of which have a ‘trapdoor’ (Figure 1) that are often extremely well disguised (J. D. Wilson et al., 2018). Trapdoor lids are almost as diverse as the animals themselves and can come in many forms, aiding in camouflaging the burrow amongst the surrounding sediment or debris (Rix et al., 2017, 2018; J. D. Wilson et al., 2018). The spiders themselves can also be cryptic in their morphology.

The females of many mygalomorph spiders are indistinguishable from one another, meaning a male is required to make morphological identifications (Castalanelli et al., 2014; Rix et al., 2018). Even when males are available, some species are morphologically identical, as in the case of some Idiosoma spiders (Rix et al., 2018).

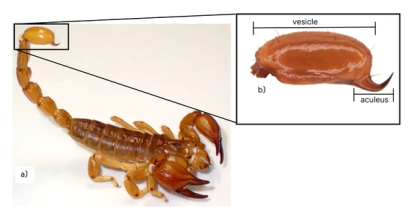

A recent project on scorpions by Buzatto et al. (2023), which began as a single species description of a morphologically distinctive animal, quickly became somewhat confusing. Multiple specimens of this previously undescribed species were held at the Western Australian Museum (WAM), all with a very distinctive bulbous telson with a short, strongly curved aculeus (Figure 2 a and b). External morphology on these specimens was consistent across all specimens, however upon dissecting out the male hemispermatophore, an internal structure used for sperm transfer and commonly used as a diagnostic tool (Angermann, 1957; Monod et al., 2017), it was discovered that this group of animals consisted of two cryptic species, indistinguishable using external morphology but with variations in internal morphology (Buzatto et al., 2023). Such challenges with morphological differentiation have led researchers to explore alternative ways to identify collected specimens, such as genetic sequencing (Castalanelli et al., 2014). This approach is becoming increasingly prevalent in environmental consulting and often relies on a combination of morphology and DNA analysis.

Taxonomy and Protection

The most prominent tool for protecting species is assigning conservation status at both state and federal levels, such as listing them as a threatened or priority species. However, the vast majority of SRE species are undescribed and therefore unknown to most people outside of a handful of taxonomic specialists (Harvey et al., 2011). As a result, the ability to conduct impact assessments on these species is limited, making it challenging to determine the need for conservation status (Harvey et al., 2011).

According to Invertebrates Australia (2025), there are approximately 100,000 described species of invertebrates in Australia, which makes up approximately 30% of the invertebrate diversity. This means there are still more than 200,000 undescribed species of invertebrate. According to the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW, 2025), Australia has an anticipated total of just over 9,000 vertebrate species, of which just over 8,000 are described. This means that in Australia, 89% of vertebrates are described, while 6.3% of vertebrates are listed as threatened. Only 30% of Australia’s invertebrates are described, and less than 0.0004% of Australia’s invertebrates are listed at the federal level. This is in fact a global issue whereby there is a reported discrepancy in biodiversity conservation research between vertebrate and invertebrate fauna (Braby, 2018; Donaldson et al., 2016).

However, as most species are undescribed and currently unknown to science, formal identification tools and a consistent, repeatable naming convention is largely absent. A contributor to the problem is a lack of taxonomic specialists with the resources to describe and nominate species for listing. To address this gap, the Western Australian Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) released a technical guidance outlining sampling techniques for SRE invertebrates (EPA, 2016), aimed at providing a framework for the protection of these highly vulnerable species. This also relied on the WAM, which set out the various SRE statuses and their definitions (WAM, 2025), with most practitioners adopting a modified version of this to assist in determining the SRE status of any given taxon. These statuses include:

- Confirmed,

- Likely,

- Potential,

- Unlikely,

- Unknown, and

- Widespread.

Placing any given taxon into one of the categories relies on several pieces of information. Understanding what and how many broad habitats any given species is collected in, and how connected those habitats are, builds understanding of the potential distribution of species. However, life history traits or microhabitat requirements may provide us with more valuable data (Harvey, 2002; Harvey et al., 2011, 2015; Rix et al., 2015, 2018; Vincent, 1993). Some trapdoor spiders rely on leaves from specific plants to construct their doors (Rix et al., 2018), while many are dependent on soil type for burrow construction (Vincent, 1993; J. D. Wilson et al., 2020). As a result, a species collected in what appears to be a widespread habitat may still be restricted in distribution based on subtle, undetectable (to humans) microhabitat characteristics.

The millipedes of southwest Western Australia are yet another example of species having restricted distributions within a broader habitat type (Car & Harvey, 2014; Moir et al., 2009). In 2009, it was reported that 89 species of native millipede were known from the southwest, of which 85 were considered to be SREs (Moir et al., 2009). This was supported in 2014 when 30 species of Antichiropus millipedes were described from the Great Western Woodlands, most of which are SRE species and can live in sympatry or have overlapping distributions with numerous other species (Car & Harvey, 2014).

The Way Forward

Understanding the factors underpinning the distribution of species will ultimately allow us to protect important habitats or microhabitats, maximising the protection of restricted-range species (Broennimann et al., 2012). This is often where environmental consultants are engaged during the development of projects. In cases where SREs are identified as a matter of importance, SRE specialists are engaged to plan and conduct surveys to collect and subsequently identify SRE species and characterise the communities. In this way, restricted range species with a higher possibility of incurring impacts associated with developments are highlighted, and management strategies put in place to inform development options and protect the species in question.

To learn more about how our team of specialists are here to help, contact us today.

References

- Angermann, H. (1957). Über Verhalten, Spermatophorenbildung und Sinnesphysiologie von Euscorpius italicus Hbst. und verwandten Arten (Scorpiones, Chactidae). Zeitschrift Für Tierpsychologie, 14(3), 276–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1439-0310.1957.TB00538.X

- Braby, M. F. (2018). Threatened species conservation of invertebrates in Australia: an overview. Austral Entomology, 57(2), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/AEN.12324

- Broennimann, O., Fitzpatrick, M. C., Pearman, P. B., Petitpierre, B., Pellissier, L., Yoccoz, N. G., Thuiller, W., Fortin, M. J., Randin, C., Zimmermann, N. E., Graham, C. H., & Guisan, A. (2012). Measuring ecological niche overlap from occurrence and spatial environmental data. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 21(4), 481–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1466-8238.2011.00698.X

- Buzatto, B. A., Clark, H. L., Harvey, M. S., & Volschenk, E. S. (2023). Two new species of burrowing scorpions (Urodacidae: Urodacus) from the Pilbara region of Western Australia with identical external morphology†. Australian Journal of Zoology, 71(1). https://doi.org/10.1071/ZO23018

- Car, C. A., & Harvey, M. S. (2014). The millipede genus Antichiropus (Diplopoda: Polydesmida: Paradoxosomatidae), part 2: species of the Great Western Woodlands region of Western Australia. Records of the Western Australian Museum, 29(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.18195/ISSN.0312-3162.29(1).2014.020-077

- Castalanelli, M. A., Teale, R., Rix, M. G., Kennington, W. J., & Harvey, M. S. (2014). Barcoding of mygalomorph spiders (Araneae : Mygalomorphae) in the Pilbara bioregion of Western Australia reveals a highly diverse biota. Invertebrate Systematics, 28(4), 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1071/IS13058

- Crews, S. C. (2023). But wait, there’s more! Descriptions of new species and undescribed sexes of flattie spiders (Araneae, Selenopidae, Karaops) from Australia. ZooKeys, 1150, 1. https://doi.org/10.3897/ZOOKEYS.1150.93760

- DBCA. (2025, September 12). Https://Www.Dbca.Wa.Gov.Au/Wildlife-and-Ecosystems/Threatened-Ecological-Communities.

- DCCEEW. (2025, September 12). Https://Www.Dcceew.Gov.Au/Science-Research/Abrs/Publications/Other/Numbers-Living-Species/Executive-Summary.

- Donaldson, M. R., Burnett, N. J., Braun, D. C., Suski, C. D., Hinch, S. G., Cooke, S. J., & Kerr, J. T. (2016). Taxonomic bias and international biodiversity conservation research. Https://Doi.Org/10.1139/Facets-2016-0011, 1, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1139/FACETS-2016-0011

- Durrant, B. (2011). Short-range endemism in the Central Pilbara. Department of Environment and Conservation, Western Australia. https://library.dbca.wa.gov.au/static/FullTextFiles/071044.pdf

- EPA. (2016). Technical Guidance – Sampling of short range endemic invertebrate fauna. http://www.epa.wa.gov.au

- Harvey, M. S. (2002). Short-range endemism among the Australian fauna: Some examples from non-marine environments. Invertebrate Systematics, 16(4), 555–570. https://doi.org/10.1071/IS02009

- Harvey, M. S., Main, B. Y., Rix, M. G., & Cooper, S. J. B. (2015). Refugia within refugia: in situ speciation and conservation of threatened Bertmainius (Araneae : Migidae), a new genus of relictual trapdoor spiders endemic to the mesic zone of south-western Australia. Invertebrate Systematics, 29(6), 511–553. https://doi.org/10.1071/IS15024

- Harvey, M. S., Rix, M. G., Framenau, V. W., Hamilton, Z. R., Johnson, M. S., Teale, R. J., Humphreys, G., & Humphreys, W. F. (2011). Protecting the innocent: studying short-range endemic taxa enhances conservation outcomes. Invertebrate Systematics, 25(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1071/IS11011

- Invertebrates Australia. (2025, September 12). Https://Invertebratesaustralia.Org/.

- Johnson, M. S., & Stankowski, S. (2018). Extreme morphological diversity in a single species of Rhagada (Gastropoda: Camaenidae) in the Dampier Archipelago, Western Australia: review of the evidence, revised taxonomy and changed perspective. Journal of Molluscan Studies, 84(4), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1093/MOLLUS/EYY040

- Johnson, M. S., Stankowski, S., Kendrick, P. G., Hamilton, Z. R., & Teale, R. J. (2016). Diversity, complementary distributions and taxonomy of Rhagada land snails (Gastropoda : Camaenidae) on the Burrup Peninsula, Western Australia. Invertebrate Systematics, 30(4), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1071/IS15046

- Moir, M. L., Brennan, K. E. C., & Harvey, M. S. (2009). Diversity, endemism and species turnover of millipedes within the south-western Australian global biodiversity hotspot 1. Durairaja Journal of Biogeography, 14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02137.x

- Monod, L., Cauwet, L., González-Santillán, E., & Huber, S. (2017). The male sexual apparatus in the order Scorpiones (Arachnida): A comparative study of functional morphology as a tool to define hypotheses of homology. Frontiers in Zoology, 14(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12983-017-0231-Z/FIGURES/35

- O’neill, C., Johnson, M. S., Hamilton, Z. R., & Teale, R. J. (2014). Molecular phylogenetics of the land snail genus Quistrachia (Gastropoda : Camaenidae) in northern Western Australia. Invertebrate Systematics, 28(3), 244–257. https://doi.org/10.1071/IS13045

- Ponder, W. F. (1997). Conservation status, threats and habitat requirements of Australian terrestrial and freshwater molluscs. Memoirs of the Museum of Victoria, 56(2), 421–430. https://doi.org/10.24199/J.MMV.1997.56.33

- Rix, M. G., Bain, K., Main, B. Y., Raven, R. J., Austin, A. D., Cooper, S. J. B., & Harvey, M. S. (2017). Systematics of the spiny trapdoor spiders of the genus Cataxia (Mygalomorphae: Idiopidae) from south-western Australia: documenting a threatened fauna in a sky-island landscape. Https://Doi.Org/10.1636/JoA-S-17-012.1, 45(3), 395–423. https://doi.org/10.1636/JOA-S-17-012.1

- Rix, M. G., Edwards, D. L., Byrne, M., Harvey, M. S., Joseph, L., & Roberts, J. D. (2015). Biogeography and speciation of terrestrial fauna in the south‐western Australian biodiversity hotspot. Wiley Online LibraryMG Rix, DL Edwards, M Byrne, MS Harvey, L Joseph, JD RobertsBiological Reviews, 2015•Wiley Online Library, 90(3), 762–793. https://doi.org/10.1111/BRV.12132

- Rix, M. G., Huey, J. A., Cooper, S. J. B., Austin, A. D., & Harvey, M. S. (2018). Conservation systematics of the shield-backed trapdoor spiders of the nigrum-group (Mygalomorphae, Idiopidae, Idiosoma): integrative taxonomy reveals a diverse and threatened fauna from south-western Australia. Zookeys, 756, 1–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.756.24397

- Vincent, L. (1993). The Natural History of the California Turret Spider Atypoides riversi (Araneae, Antrodiaetidae): Demographics, Growth Rates, Survivorship, and Longevity on JSTOR. The Journal of Arachnology, 21, 29–39.

- WAM. (2025, September 12). Https://Museum.Wa.Gov.Au/Catalogues/Waminals/Sre-Status.

- Wilson, J. D., Hughes, J. M., Raven, R. J., Rix, M. G., & Schmidt, D. J. (2018). Spiny trapdoor spiders (Euoplos) of eastern Australia: Broadly sympatric clades are differentiated by burrow architecture and male morphology. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 122, 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YMPEV.2018.01.022

- Wilson, J. D., Raven, R. J., Schmidt, D. J., Hughes, J. M., & Rix, M. G. (2020). Total-evidence analysis of an undescribed fauna: resolving the evolution and classification of Australia’s golden trapdoor spiders (Idiopidae: Arbanitinae: Euoplini). Cladistics, 36(6), 543–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/CLA.12415

Recent posts

-

-

Unlocking value through solar PV repowering: A focus on module replacement and DC/AC optimisation

by David Fernandez

View post -